Google Analytics is a powerful tool that allows users to analyze data through a variety of customizable ways. The tool gets its power from the flexibility that it is built into it. However, that flexibility sometimes results in unintended complexity.

In this post, I will highlight some of the common misconceptions experienced in using Google Analytics.

Traffic Attribution

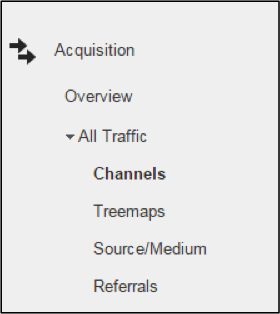

Google Analytics categorizes site traffic in easy-to-understand channels, such as organic search, referral, and email. The easiest place to find this categorization is in the channels report under Acquisition > All Traffic.

Google Analytics categorizes site traffic in channels, such as organic search, referral, and email.

Google has documented how it determines these channels. In a nutshell, the channel definitions rely on values set in “source”’ and “medium” variables. For example, if the medium for a session is set to “organic,” then the session will be recorded as having originated from Organic Search — i.e., Google, Bing, Yahoo.

Another channel is “Direct.” In technical terms, direct constitutes traffic where the medium is not set or is none. So it is traffic from sources other than organic search, paid search, social media, and other channels. This direct bucket typically constitutes traffic where users directly type a website’s URL into their browser’s address field or visit a website using bookmarks.

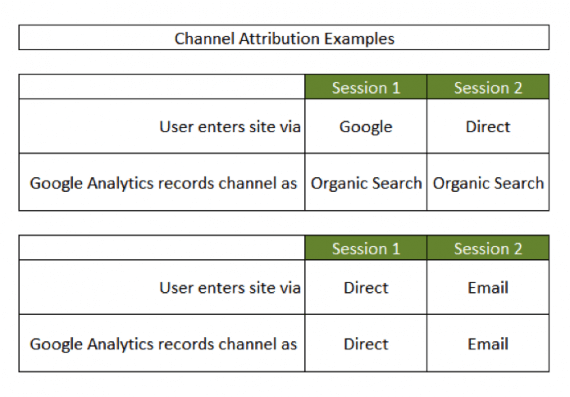

However, in reality it is more complicated. If a user has recently visited a site through organic search, referrals, or from a campaign (such as email), then even if the user visits the site a second time as a “direct” visitor, the session is attributed to the previous non-direct channel. Below is an illustration to explain this further.

If a user has recently visited a site through organic search, referrals, or from a campaign (such as email), then when the user visits the site a second time as a “direct” visitor, the session is attributed to the previous non-direct channel.

From the example image above, the direct channel gets the lowest priority in attribution. If a user first visits a site from a non-direct channel, subsequent direct visits also get attributed to the non-direct channel. Conversely, if a user is first a direct channel visitor, subsequent non-direct visits are attributed to non-direct channels.

This means that traffic data for organic search, email, and other non-direct channels may actually be overstated. While one could argue that it isn’t really inflated and instead provides more accurate attribution, it does understate brand-aware traffic by attributing it back to the previous non-direct source.

User vs. Session Measurements

Google defines a session as “a group of interactions that take place on your website within a given time frame.” What’s not as obvious, however, are the implications of using sessions versus users in creating segments and reports in Google Analytics.

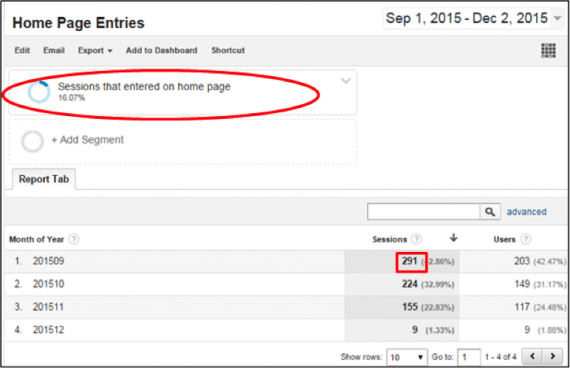

Consider the example below. To know trends for traffic entering on the home page, one could look at the data from a session or user perspective.

This report shows a sessions-based segment for home page visits.

The above report shows users and sessions by month for the last three months. It uses a sessions-based segment to select sessions that entered on the home page. Note that the session count for September 2015 is 291. The report below is exactly the same, except that it uses a segment that is designed to select users entering the home page.

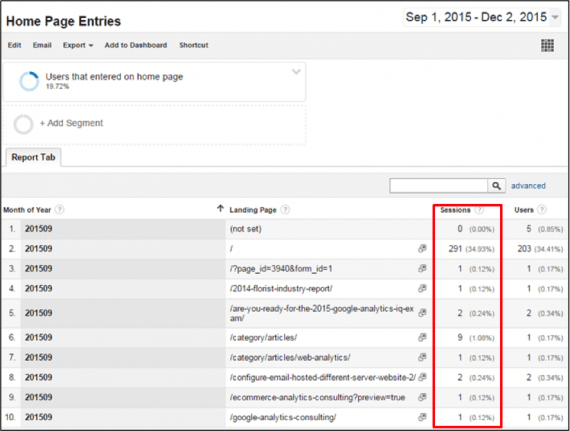

This report shows a users-based segment for home page visits.

In this report, the session count for September 2015 is 394 — different from the 291 measured when using the session-based segment.

The session segment selects all sessions that entered on the home page. These sessions don’t recur and don’t influence how subsequent sessions are measured. On the other hand, the user segment selects users that entered the site through the home page at some point in that month. Those same users could have come back at different times in the month and created multiple session counts.

The report below provides further insight into this phenomenon. The only change to the report from the version above is that this report now shows the pages that the sessions started on. In addition to the 291 sessions that actually started on the home page, there are several other sessions that didn’t start on the home page. The reason they get counted is because these same users had entered on the home page at some point in the month of September.

This report shows the pages that the sessions started on. Sessions that didn’t start on the home page get counted because these same users had entered on the home page at some point in the month of September.

These concepts are not obvious to casual users of web analytics.

Referral Traffic

Traffic that enters the site from sources other than search engines, campaigns, or social media is categorized as referral traffic. Incorrectly categorized referral traffic is common in Google Analytics. There are three parts to this problem.

- Incorrect sources of referrals. For some ecommerce sites, the checkout portion of the sales funnel may be set up on third-party domains. In particular, payments made on PayPal require re-direction to the PayPal servers that then automatically direct users back to the site once the payment is complete.

Because of this break in tracking, users returning from these third-party servers are categorized by default as referral traffic. This problem can easily be solved by adding these domains to an exclusion list.

- Self-referrals and subdomain traffic. Sometimes the parent domain appears as a significant source of referrals. In addition, if the site is set up across a series of subdomains — such as a http://blog.yoursite.com, http://info.yoursite.com, http://www.yoursite.com — then these subdomains may also cause self-referral issues.

The root cause of such problems typically is incorrect tracking code on pages that show up as referral sources. Correct this by auditing Google Analytics tracking code regularly across all subdomains and pages.

- Referral spam. An ongoing issue with Google Analytics tracking is the disruption of measurement because of referral spam. This is caused by spammers that identify a site’s Google Analytics tracking code, and then use automated bots to fire that tracking code, thus causing Google Analytics to record a session when, in fact, a session has not occurred — the bot merely accessed the tracking code, maliciously.

Such spam causes referral traffic to inflate and significantly disrupts the use of Google Analytics. Creating filters that exclude these domains and maintaining updated segments that exclude referral spam traffic can help reduce the issues caused by referral spam.

Case Sensitivity

Google Analytics is case sensitive. In other words, it interprets “Hello World” and “hello world” as two distinct phrases. The implications of this are far reaching. Any user-driven input needs to be consistently lowercase or consistently uppercase. Here are some problem areas if the case is not carefully used.

- Campaigns. When campaign parameters such as utm_campaign and utm_source are used to track the source of referral traffic, the values of these parameters need to be carefully examined.

For example, if a marketer sets the utm_campaign value to “ThanksgivingSale” for one URL and to “ThanksGivingSale” for another, Google Analytics will record these as two separate campaigns. The solution to this problem is to apply filters to catch inadvertent case changes.

- URLs. While marketers may control campaign parameters, they may not control over how a URL gets shared. If a URL was shared in all uppercase but it primarily exists as a lowercase URL, then Google Analytics will show two distinct URLs in its page reports.

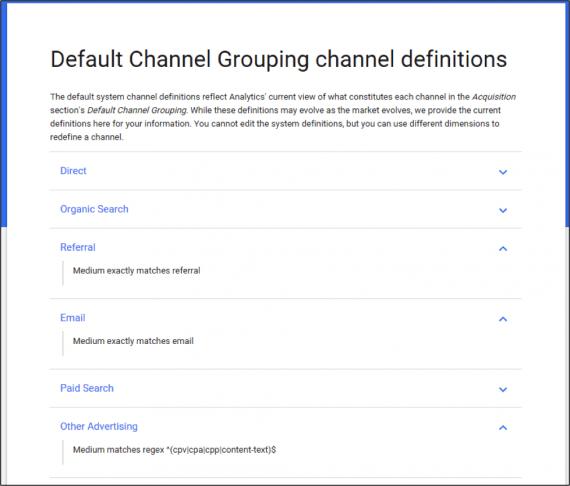

- Channel grouping. Google Analytics groups sources of traffic into default channel groupings for easy reporting. The text of these channel names cannot be directly edited. So if the value of the “medium” parameter is set with an uppercase letter, the channel will not appear in the default channel grouping report. Here is a screenshot that shows the channel names and their “definitions,” as set by Google.

Google Analytics groups sources of traffic into default channel groupings. The names of these groups cannot be edited and Google defines how the text — upper and lower case — should be used.

For example, under the “Email” channel, Google requires the text of that medium to be “email” — lowercase. If the text is set to “Email” — uppercase E — then Google Analytics will not display it in the default channel report. Instead, it will show up under a new category, “Other.”

Flexibility vs. Complexity

Google Analytics provides a highly flexible interface to analyze data. However, that flexibility also introduces nuances and complexity that users need to be aware of when using it. While none of these issues described above are difficult to solve, they can occur without warning. Hence, Google Analytics users should regularly monitor their data, to ensure quality reporting.