In 1998, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, intended to extend intellectual property rights to the web and to limit liability for online service providers.

Since then, search engines have used their web crawlers to identify and copy millions of available web pages to their own servers, which they then organize for display on search results. Without this service, website owners would be bound strictly to direct traffic, but the process of copying everything on the Internet has caused serious disputes over who controls content and exactly what constitutes a copyright infringement.

How Indexing Works

Google’s Quality Engineer Matt Cutts has offered a detailed explanation of how Google indexes and arranges search hierarchies.

A simplified version is this: Google’s spider program crawls the billions of pages on the web by connecting to servers and requesting pages. It then follows hyperlinks on those pages to new pages. Each page is given a number for reference.

The next step is indexing. Google creates a list of every page retrieved in the crawl that contains a specific word and organizes the pages based on the numbers it assigned during the crawl. It stores this index on hundreds of computers to expedite the process of matching search queries to pages that contain those words.

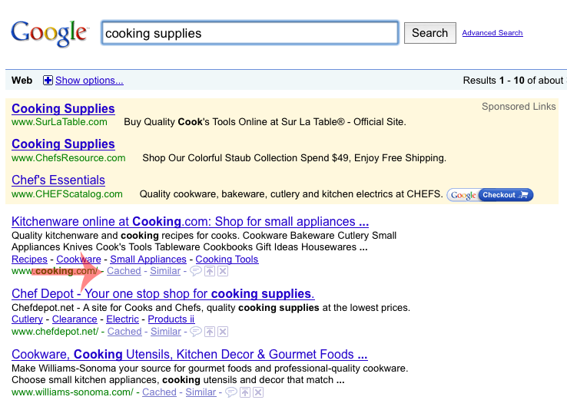

In addition, Google stores an archived version on its own servers of every website it indexes. Google calls this the “cached” version of these websites and the word “Cached” appears next to the organic search results. Users can therefore click on the direct links to a website or on the “Cached” version, which is stored on Google’s servers.

Screen capture of Google search results for “cooking supplies,” highlighting a “Cached” link in the results.

Google makes large profits by copying and indexing the content of websites and then selling pay-per-click ads linked to that content. Some large media companies have realized the value of threatening to opt out of the index. The Associated Press, for example, was reportedly able to get Google to pay it for indexing rights.

However, for ecommerce merchants, the primary concern for their content is attracting potential customers. If it comes to a bidding war between two deep-pocketed search engine companies for the rights to index online content, merchants will likely continue to focus on making their stores as visible as possible, regardless of what search engine a customer uses.

Does Indexing Violate Copyright Laws?

Ken Auletta, a long-time writer for The New Yorker magazine, published a book this year called Googled: The End of the World as We Know It. In it, he analyzes Google’s effect on the media industry and the copyright implications from indexing content from those media companies. CSPAN, the cable news channel, recently interviewed Auletta about his new book.. He quotes Columbia Law professor Timothy Wu, who states there has never been a case that establishes whether indexing a page is copyright infringement.

But in a 2006 case, a U.S. district court in Nevada decided Google’s caching (which follows from Google’s indexing process) of web pages does not violate copyright law. The plaintiff in the lawsuit, Blake Field, had filed a complaint that when Google cached one of his works published on his personal page, it violated intellectual property rights.

Google maintained that users could stop their pages from being indexed by creating file that blocks the search engine’s automated crawlers. They can also opt out of having their content cached. By not opting out, a site owner gives Google implied license to copy the pages.

The court agreed, ruling also that Google was protected under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which removes liability for search engines and other online service providers under certain conditions.

Bing and the Battle for Content

News Corp., the media company controlled by Rupert Murdoch, is reportedly working on a deal with Microsoft to allow Bing exclusive indexing rights to all News Corp content. This means the websites of The Wall Street Journal, Fox News and many large, News Corp.-owned newspapers will not show up in a Google search if the deal goes through.

Many have speculated about the precedent this could set for search engines bidding against each other, which could provide a site owner with a way to monetize his or her content other than through advertising or paid subscriptions.

For media publishers like Murdoch, who has accused Google of stealing content, enticing the two search engines to bid is a valuable option.

For ecommerce merchants, the choice of whether to sacrifice organic search traffic is presumably a no-brainer. While media companies see their online content as a valuable product in itself, merchants primarily use their online content for marketing and to make sure their sites are visible on search engines. They presumably would rather have as much traffic to their sites as possible and would therefore encourage the indexing and copying of it from the search engines.

Microsoft has been trying to get more of the shopping-search-market share through its Bing Cashback program. U.S. e-merchants can sign up to offer customer rewards through Bing’s shopping comparison engine. Cashback is based on a cost-per-acquisition model that allows merchants to decide the percentage of the purchase given to the customer as a reward.

Bing does not seem to be seeking the same kind of exclusivity with online retail as it is with News Corp. Many Bing Cashback stores also have products listed on Google Product Search, and even its biggest Cashback retailers like Bn.com, Kohls.com and Footlocker.com have not, to our knowledge, been asked to exclude Google. And because these merchants use their sites to sell products instead of selling their sites as products, it’s unlikely that they ever will.

Banning Search Engines is Easy

Some media companies seem to be taking different stances on whether search engines should pay them for the right to link to their stories. Reuters President Chris Ahearn wrote recently that he supports free indexing and linking.

“I don’t believe you could or should charge others for linking to your content,” Ahearn wrote. “If you don’t want search engines linking to you, insert code to ban them.”