Founded in Chicago in November 2008, Groupon filed to go public last month after reportedly rejecting a $6 billion takeover offer from Google last December. As with other recent filings by ecommerce firms, a few surprises emerged. Groupon is a pioneering marketing company that has achieved spectacular growth in a short period of time. The subscriber base grew from 152,200 as of June 30, 2009 to 83.1 million worldwide as of March 31, 2011. The company sold 116,231 Groupons in the second quarter of 2009 compared to 28.1 million in the first quarter of 2011. The number of participating merchants increased from 212 in the second quarter of 2009 to 56,781 in the first quarter of 2011.

Andrew D. Mason, Groupon’s CEO, took the unusual step of including a letter full of bravado in the S-1 filing saying, “We don’t measure ourselves in conventional ways,” and “We are unusual and we like it that way.” We will soon see if investors like it that way.

Business Model

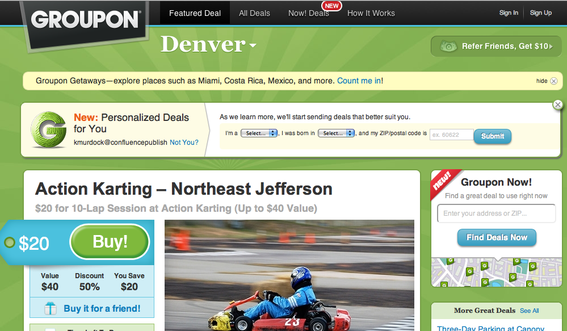

Each day Groupon sends email subscribers deeply discounted offers for goods and services tailored to their geographic locations and personal preferences. Consumers can also access deals directly through the Groupon website and mobile applications. Merchants sign up with Groupon and offer a discount — usually 50 percent — to a certain number of people for a limited amount of time. Groupon creates a sense of immediacy by requiring that a minimum number of consumers buy the deal within a specified time frame, or the deal is canceled. All revenues are split between the merchant and Groupon, usually 50/50.

Financials

Groupon hopes to raise a minimum of $750 million with the stock sale. The company could be valued at $30 billion at its public debut, more than Google’s $12 billion initial-public-offering valuation. Revenue grew from $3.3 million in the second quarter of 2009 to $644.7 million in the first quarter of 2011. Total 2010 revenue was $713.4 million. However, Groupon has never turned a profit. The company spent $263.2 million on marketing in 2010, an enormous increase (5,687 percent) over the $4.5 million it reported for 2009. Marketing expenses as a percentage of revenue for the years ended December 31, 2009 and 2010 were 14.9 percent and 36.8 percent respectively. The company attributed the significant increase to more aggressive online marketing, particularly on social networking websites and search engines as part of a new subscriber acquisition strategy.

In keeping with its pledge to measure itself in unconventional ways, Groupon has made up its own metric — something called “adjusted consolidated segment operating income” — that excludes marketing and acquisition costs. This metric, which is not compliant with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), allows the company to show an operating profit when, in fact, it had a net loss of $413.4 million in 2010 and $113.9 million in the first quarter of 2011. Google, in contrast, was highly profitable when it went public.

Take the Money and Run

Some interesting events have occurred over the past seven months. After Groupon spurned Google’s bid, it received a new round of venture capital financing in January worth $950 million. Only $136 million of that money was directed towards the business. The rest was used to buy shares from CEO and co-founder Andrew Mason, co-founder Eric Lefkofsky, and others. Lefkofsky received over $300 million. Mason still owns around eight percent of the company, while board chairman Lefkofsky is the main shareholder with almost 22 percent. Robert Solomon, president and chief operating officer, left the company in March, redeeming some stock but maintaining over 1.6 million shares.

That was curious timing for a company that likely decided it would go public when it rejected the Google offer. Shares would presumably be worth more after the IPO. One conclusion that could be drawn is that the insiders realize the valuation of the company has already exceeded its actual worth or its potential. Groupon is a company that might not see a profit for a very long time. It took Amazon seven years to achieve a profitable quarter but investors today are not quite as patient.

The S-1 filing states, “We anticipate that our operating expenses will increase substantially in the foreseeable future as we continue to invest to increase our subscriber base, increase the number and variety of deals we offer each day, expand our marketing channels, expand our operations, hire additional employees and develop our technology platform. These efforts may prove more expensive than we currently anticipate, and we may not succeed in increasing our revenue sufficiently to offset these higher expenses.”

Competitors

Living Social, which operates on a similar model but takes only a 40 percent share of revenue from merchants, has been growing steadily and will probably issue its own IPO soon.

Google and Facebook will probably enter the coupon business and both have enough money to scale rapidly. They can probably offer merchants a larger percentage of revenues as well, thereby taking merchants away from Groupon.

Merchant Problems

One aspect of the model that has burned some merchants is that the more successful the promotion, the more money the merchant loses because of the deep discount Groupon encourages. A blog post by Posies Bakery and Café in Portland, Oregon tells of the owner’s experience. The shop’s aggressive deal ($13 worth of merchandise for $6 with a 50/50 split) over three months cost the business $8,000.

Rice University’s Jones School of Business conducted a study of 150 businesses that participated in a Groupon promotion. The coupon campaigns were unprofitable for 32 percent of the businesses that ran them. More than 40 percent of the response group said they would not run another social coupon promotion again. For these campaigns to be successful, according to the study’s author, customers redeeming the coupons have to spend more than the coupon amount, and come back again to shop without a coupon offer.

That’s the point proponents of Groupon assert: The merchant’s coupon cost is best viewed as advertising, customer-acquisition expense. Viewed in this light, the proponents say, using Groupon to acquire new customers can be effective, and, indeed, that is the view of Murat Goker, a Groupon customer that we profiled last month, at “One Merchant’s Experience with LivingSocial and Groupon.”

Groupon’s Challenges

- Shrinking margins. The cost to acquire new subscribers is growing enormously and Groupon’s margins are already declining.

- Need new merchants. To continue to grow, Groupon must add new merchants. If more merchants have unsatisfactory experiences with Groupon, the company will stall. The S-1 filing states, “We depend on our ability to attract and retain merchants that are prepared to offer products or services on compelling terms through our marketplace. We do not have long-term arrangements to guarantee the availability of deals that offer attractive quality, value and variety to consumers or favorable payment terms to us. We must continue to attract and retain merchants in order to increase revenue and achieve profitability.”

- Few barriers to entry exist. Groupon can expect new start-ups to spring up and face new competition from companies with a lot of cash to burn such as Facebook and Google.