Editor’s Note: We welcome Jeremy Hanks as our newest contributor. He is a serial tech entrepreneur, having launched two drop-shipping-related companies: Doba and, most recently, DropShip Commerce. For us, Hanks will address drop-shipping and ecommerce supply chain matters. His first piece, on the evolution of the supply chain, is below.

To fully address the good and the bad of drop shipping as a supply management technique, I’m going to start with the history and current state of the retail supply chain.

Inventory Distortion

According to a recent report from IHL Group, a research and advisory firm, nearly $1.5 trillion of worldwide merchandise annually is in an overstock position that creates a loss in revenue. Losses due to deeply discounted overstocks amount to $362 billion per year. Out-of-stock inventory is an even bigger problem with annual losses of $456 billion. Together, that’s over $800 billion in annual losses per year. These losses are growing by almost $50 billion per year because of a lack of infrastructure to handle retail growth in emerging economies. These numbers also do not include losses from “unstocked” inventory: those products that were never even selected by retailers as inventory.

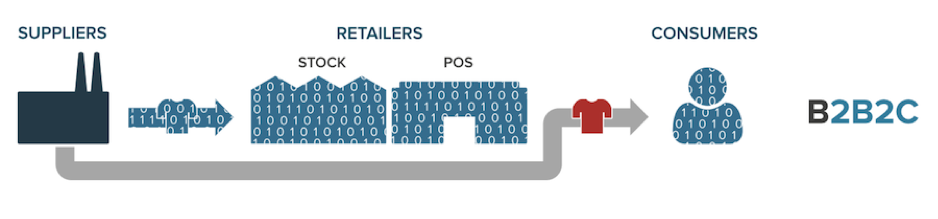

Traditional supply chains typically involve suppliers (manufacturers), retailers, and consumers.

It’s called inventory distortion. Prior to 1994, retail supply and demand developed inside of the geographic constraint of consumers and the physical constraint of inventory, for four reasons: (a) Retailers could only sell to consumers who lived near their stores; (b) Consumers could only buy products that retailers in their area chose to carry in their stores; (c) Those stores had four walls and a ceiling that could only fit a finite amount of physical products; and (d) Even if physical space wasn’t the constraint, money to purchase inventory quickly was.

The retail supply chain evolved to serve these constraints. Manufacturers built what retailers ordered and shipped them to physical retail stores. The roles of business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) were very discrete and delineated, with few exceptions. It resulted in limited product penetration for the brands and manufacturers, fewer sales for the retailer, and less choice for the consumer. It was an inefficient, product-push, and predictive supply chain.

Ecommerce

With the advent of ecommerce, demand was no longer limited by geographically-constrained consumers.

The Internet allowed any given retailer, large or small, to sell to consumers potentially anywhere in the world. Retailers were no longer constrained by the restrictions of physical store as their point of sale. Their ability to aggregate demand greatly increased, and in response, online retailers scaled increased their inventory. But they often followed the traditional supply chain model by aggregating inventory in centralized distribution centers while maintaining the dynamics of the older B2B roles and business models. While ecommerce removed the geographic constraints for B2C, physical inventory constraints where only shifted and still greatly restricted product supply in a world of now nearly limitless paths to consumer demand. Inventory distortion remained.

Supply Chain Evolution

- Drop shipping and marketplaces. From the early days of ecommerce, economists started researching what would happen if you could further push virtualization back upstream into the supply side.

Ecommerce facilitates a “virtualized third party” (i.e., suppliers) that can sell directly to consumers.

Because the consumer wasn’t physically at a point of sale, if you could capture product data and have inventory visibility to a manufacturer’s or distributor’s product stock, the suppliers could then hold inventory until a consumer sale originated and then fulfill directly to the customer on behalf of the retailer. This is called “drop shipping.” It’s also called inventory free retail, endless aisle, and the silver bullet to fast, easy, and instant ecommerce riches.

Marketplaces evolved later and enabled even greater scale of virtual product supply because through vendor transparency, rather than blind fulfillment, the marketplace was able to put the work of sourcing new vendors onto the shoulders of those very vendors who had the physical product supply.

- Manufacturer direct-to-consumer. Before ecommerce, the companies who create the products — brands and manufacturers — have desired to sell directly to the consumer. With the web, and with manufacturers’ ability to launch an ecommerce storefront just as retailers were doing, they could actually do it.

Ecommerce and the social web finally enabled mass direct-to-consumer adoption by suppliers.

Selling directly to consumers creates conflict — i.e., “channel conflict” — with retailers. For years, most manufacturers wouldn’t touch direct-to-consumer for fear of alienating their base of retail dealers.

But think of these developments from a manufacturer’s or distributor’s point of view.

- A large number of retailers, especially large ones, were consistently asking you to support drop shipping — by creating consumer-ready online product content, and implementing single item order fulfillment and logistics — so that they could increase their product assortments without buying the inventory.

- The Great Recession of 2008 happened, and your B2B business suffered as retailers reduced wholesale orders or went out of business.

- Facebook and other social networks unlocked a scalable and direct way to connect with loyal fans and customers, and once connections started happening, commerce was soon to follow.

In short, it’s becoming increasingly rare to find manufacturers that don’t sell directly to consumers, in addition to their B2B channels.

Trends Now and For the Future

There are two macro trends that are impacting the supply chain.

- Internet-based supply and demand.

- The ability for scalable direct-to-consumer models where traditional players can be removed from the equation.

Both of these trends speak to the consumer connecting upstream into the supply chain. In other words, the elimination of the geographic constraints on consumer demand through ecommerce and the Internet is leading to the removal of the physical barriers of supply with distributed inventory and advanced supply chain strategies.

Drop Shipping: Legit? Hype? Scam?

If you make things, you have a product penetration problem. If you sell things, you have a product selection problem. For both, inventory is distorted and supply and demand are inefficient. The reason drop shipping has received so much attention in the past 15 years is because, in it’s purest form, it strikes at the core problem of inventory distortion inside of the traditional supply chain.

Drop shipping can be good for manufacturers and suppliers because it increases product exposure and penetration through existing or new channels. It can be good for retailers because it reduces inventory risk while increasing product selection. And it can be good for consumers who can find the products they want to buy from the company where they prefer to shop.

See the next installment of “Drop Shipping for Ecommerce” at “Part 2: The Basics.”