If you think buying stock in a public company guarantees you some input into how the company operates and who is elected to the board, you may be mistaken. Thanks to a change in stock exchange rules made over 30 years ago that is increasingly being used by companies going public, shareholders with common stock — even large institutional ones — have little influence over how the company is governed.

History

From 1940 until 1986 the New York Stock Exchange did not list companies with dual-class voting. The rule was changed in response to a request from General Motors. Shareholder rights in the U.S. are largely regulated by states, and it is the stock exchanges, not the Securities and Exchange Commission, that have been making the rules.

If you think buying stock in a public company guarantees you some input … you may be mistaken.

For the next 20 years, few companies that issued IPOs implemented the dual-class system. Then, in the early 2000s, technology companies issuing IPOs latched onto dual-class shares as a way to maintain all the benefits of being private companies while getting a large influx of public money.

Currently Nasdaq, NYSE, and NYSE American (formerly American Stock Exchange) each permit dual-class stock listings by corporations as long as the dual-class structure is in place at the time of the IPO.

Most foreign stock exchanges do not allow dual-class stock structures. When Chinese ecommerce behemoth Alibaba decided to go public in 2014, it bypassed the Asian stock exchanges and listed on the NYSE. It was the largest IPO in history at a $21.8 billion valuation.

An article in Columbia Law School’s “Blue Sky Blog” in July 2018 stated, “From 2005 to 2015, the proportion of initial public offerings that created dual-class share structures rose from a mere 1 percent to 24 percent. More than half of all U.S. technology, media, and telecommunications companies that issued an IPO in 2015 chose a dual class structure.”

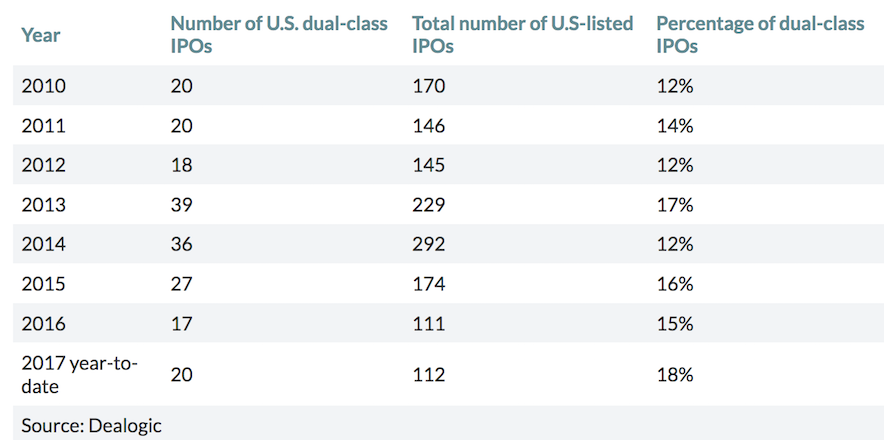

Dual class IPOs rose from 12 percent of the total in 2010 to 18 percent for 2017, through September. Source: Dealogic.

Companies with dual-class shares include:

- Alphabet (the parent company of Google),

- Berkshire Hathaway,

- Box,

- Comcast,

- Fitbit,

- Ford Motor Company (which was allowed to float dual-class shares in 1956 despite it being against American Stock Exchange rules),

- Groupon,

- LinkedIn,

- Netflix,

- UPS,

- Wayfair,

- Zynga.

Dual Class: Pros, Cons

An argument for dual-class stock is that founders know best how to run their companies and allowing them to have majority control provides stability and more revenue and profit.

However, if there are no sunset provisions for the dual-class shares, they can be given to founders’ heirs who may know little about the business and yet get unfettered decision-making power.

Furthermore, there is scant evidence that companies that have a dual-class structure do better than other public companies.

Moreover, dual-class shares are undemocratic. Critics say one share, one vote is the right approach because public investors accept a portion of the risk when they buy stock and they should be able to vote for change if management falters. When insiders are left to oversee themselves, poor performance can go unchecked.

The boards of directors of dual-class companies are usually filled with company founders and employees and original venture capital investors. Some dual-class boards have no independent members. Sometimes this is intentional. Nonetheless, a dual-class structure can limit a company’s ability to attract independent board members.

SEC Weighs In

SEC Commissioner Robert Jackson Jr., appointed early in 2018, has taken on the dual-class conundrum. He says he understands the benefit of a dual-class stock in the early years of a public company, but he is a foe of perpetual inequity.

In a speech earlier this year he asked, “Should our public investors have to place eternal trust in corporate insiders? That is, should so-called perpetual dual-class stock ownership structures, which grant corporate executives control of our public companies literally forever, be acceptable?”

“Should our public investors have to place eternal trust in corporate insiders?”

He believes shares that come with exorbitant voting rights should eventually expire and become ordinary stock, to avoid what he calls “corporate royalty.”

Another SEC Commissioner, Kara Stein, chimed in, voicing her concerns in a 2018 presentation where she stated that dual-class shares “provide a means to evade management and board accountability.”

Opposition Grows

The Council of Institutional Investors, a non-profit association whose members include public pension funds, recently called for dual-class listings to be removed from equity indexes. It stated that “every share of a public company’s common stock should have equal voting rights and no-vote shares have no place in public companies.”

As of September 2017, index compiler FTSE Russell excludes all companies whose public shares constitute less than 5 percent of total voting power while S&P Dow Jones will now exclude all dual-class firms.

In July of this year, after the Facebook annual shareholders meeting, the largest pension fund in the country, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, said the dual-class structure permitted the data hacking debacle and resulting privacy scandal at Facebook to happen because Mark Zuckerberg, who owns 1 percent of shares but has 60 percent of the votes, chose to ignore or deny the hacking for many months. CALPERS asked that the structure be eliminated. The second largest pension fund, California State Teachers’ Retirement System, issued a statement saying that Facebook’s governance “is now akin to a dictatorship.”

New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, who manages $895 million of Facebook shares in the City’s pension fund, said, “We have concerns about the structure of the board that the company doesn’t seem ready to address, which can lead to risks — reputational, regulatory, and otherwise.”

Other investment funds suggested that the chairman role and the C.E.O. role — both held by Zuckerberg — be separated and that Zuckerberg step down as chairman. Facebook’s response was that such a move would cause “uncertainty, confusion, and inefficiency in board and management function,” despite the fact that more than 50 percent of public companies separate the chairman and C.E.O. positions.

Another company that inflamed the situation earlier this month is photo-sharing firm Snap Inc., owner of Snapchat. The two founders of the company, which went public in 2017, hold 96 percent of the voting rights and give public stockholders no voting rights at all. That made the company ineligible for the S&P 500 Index. The IPO stock price was $17. As of August 14, 2018, it was trading at $12.34.

Snap lost over $700 million in its first year as a public company yet Snap’s C.E.O. Evan Spiegel received a $638 million bonus. At the end of July 2018, Snap held a three-minute annual shareholders meeting online with neither of the founders or any employees attending. An attorney read a statement and ended the meeting.

Snap held a three-minute annual shareholders meeting online with neither of the founders or any employees attending.

Solving the Problem

Many pension funds and the Council of Institutional Investors recommend sunset clauses for dual-class shares a few years after an IPO. Evidence suggests that companies with sunset clauses over time do better financially than those without one. Others who view the practice as fundamentally undemocratic want a ban on the dual class system.

Either way, the consensus is that some regulation is necessary, as more companies are employing this system that shuts out the public investor.