Entrepreneurs and managers who lead emerging companies often make critical decisions based on imperfect data and a gut feeling.

Most, if not all, companies seek “data-driven” decisions. When it launches a new product, updates its branding, or defines its focus, a company desires excellent market intelligence.

Unfortunately, excellent intelligence rarely exists. Human bias affects data interpretation. But we still have to make decisions. To understand the complexity, consider a couple of decision-making frameworks.

Information-action Paradox

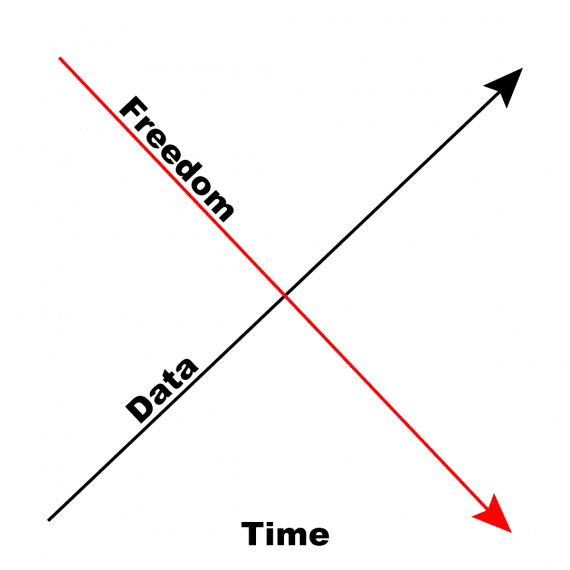

In business, it is often the case that the more public a market trend, an opportunity, or a customer segment, the less freedom we have to act.

As the authors of a recent Harvard Business Review article put it, when “data is widely available…others see the same opportunities and risks and respond to them.”

The information-action paradox implies that the freedom to act on information and its public availability are inverse.

A new entrepreneur can make a decision based on relatively sparse public data, an inkling of a trend. She has little information but plenty of freedom to choose.

An incumbent business must often wait for more public data since its managers can rarely act unilaterally but must get buy-in from superiors, peers, and subordinates. These leaders must work through a process of coaxing and convincing, often waiting for additional data. Frequently, such companies have more info for strategic decisions but relatively less freedom to act since competitors will also be aware of the opportunity.

This paradox might lead some managers to act quickly, ahead of competitors.

Diderot Effect

Decisions based on little-known data could lead to opportunity, but they require executives to trust their gut stemming from experiences and feelings.

Human psychology becomes a factor.

Here’s a real-life example. A software-as-a-service company in the process of repositioning itself decided to focus on mid-sized customers. It made the choice with relatively little public information. But because it is smallish, the company had significant freedom to act.

The decision impacted several managers and their departments.

It prompted one manager to conclude she must stop concierge support to 20 of the company’s largest and most profitable customers since those enterprises were no longer the focus.

Ignoring very profitable customers because they do not fit with the company’s perceived strategy is reminiscent of the Diderot Effect in buying.

Denis Diderot was an 18th-century French philosopher. Among his many influential works is a lean essay about a new red robe, titled “Regrets for my Old Dressing Gown, or A warning to those who have more taste than fortune.”

Diderot got a fancy new robe and ultimately redecorated his entire study with expensive art and furniture because the fine robe made the room feel uncoordinated and ugly. Diderot was less happy despite the new possessions.

In the late 1980s, cultural anthropologist and author Grant McCracken used Diderot’s essay to illustrate two human tendencies, which he collectively called “the Diderot Effect.”

- Purchase decisions are not always rational; we buy things that match our identity.

- A new possession, like Diderot’s robe, can redefine our identity, prompting us to make subsequent and unnecessary purchases that conform to it.

The BBC has an excellent explainer video describing the Diderot Effect.

More recently, author James Clear used the Diderot Effect in his book “Atomic Habits” to describe how personal identity impacts choice and routine.

Thus the Diderot Effect describes buying behavior and habit formation, but it could also affect business decisions.

Hence the SaaS manager was willing to stop servicing 20 of a company’s best customers because that decision matched her perception of the business’s identity.

Balance

The information-action paradox and the Diderot Effect are present when a company makes strategic decisions.

The information-action paradox implies that business leaders should act when they have more freedom, taking advantage of opportunities before their competitors.

But the Diderot Effect implies that we should pause to understand what motivates those decisions.

So here is the good news. Business leaders who recognize these forces can account for them, striking a balance. When considering a strategic decision, look at both: the data and the influences.